The Issues

Know the facts

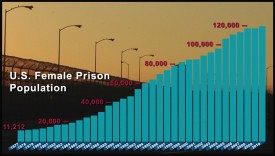

Over the last 25 years, women have represented the fastest growing sector of America’s prison population. The majority of women behind bars today are survivors of domestic violence — victims of rape, incest, forced prostitution, and other exploitation. In many cases, the abuse they suffered led to their alleged transgressions. Among the most extreme examples are cases in which a battered woman kills her abuser.

Meanwhile, the soaring costs of incarceration and the depth of the current economic recession are forcing many states to reconsider their sentencing guidelines and parole policies. In this context, the release of incarcerated survivors of abuse, many of whom have been imprisoned for decades and whose only crime was fighting for their own survival, represents a significant and politically feasible step towards reducing prison populations and restoring justice.

Meanwhile, the soaring costs of incarceration and the depth of the current economic recession are forcing many states to reconsider their sentencing guidelines and parole policies. In this context, the release of incarcerated survivors of abuse, many of whom have been imprisoned for decades and whose only crime was fighting for their own survival, represents a significant and politically feasible step towards reducing prison populations and restoring justice.

CRIME AFTER CRIME tells the dramatic story of the effort to free Debbie Peagler, an incarcerated survivor of brutal domestic violence. Through her legal case, a grassroots campaign to secure her release, and media coverage of her saga, Debbie’s journey shines a light on a population that has largely been ostracized and denied justice by American prisons and courts. Her story shows us a way forward in healing the troubled intersection of domestic violence and criminal justice in the United States.

CRIME AFTER CRIME tells the dramatic story of the effort to free Debbie Peagler, an incarcerated survivor of brutal domestic violence. Through her legal case, a grassroots campaign to secure her release, and media coverage of her saga, Debbie’s journey shines a light on a population that has largely been ostracized and denied justice by American prisons and courts. Her story shows us a way forward in healing the troubled intersection of domestic violence and criminal justice in the United States.

As misguided funding cuts now force the closure of battered women’s shelters and recreate a situation in which victims have no safe way to escape abuse, this film becomes all the more crucial. The project exposes widespread problems in prosecution and sentencing, demonstrates the grounds for the release of incarcerated survivors of domestic violence, and advocates for the correction of unfair criminal justice practices.

Most women in prison are survivors of domestic violence.

Unfortunately, our justice system does little to track whether or not someone charged with a crime is a victim of domestic violence. Research has shown, however, that especially for women and children, domestic violence or other abuse often is a factor in an alleged crime. Sometimes the link is direct, such as when a battered woman fights back against her abuser. Other times, the link is indirect, as in the case of an abused teen who turns to drug use to numb the physical, emotional, and psychological wounds brought on by the abuse.

Unfortunately, our justice system does little to track whether or not someone charged with a crime is a victim of domestic violence. Research has shown, however, that especially for women and children, domestic violence or other abuse often is a factor in an alleged crime. Sometimes the link is direct, such as when a battered woman fights back against her abuser. Other times, the link is indirect, as in the case of an abused teen who turns to drug use to numb the physical, emotional, and psychological wounds brought on by the abuse.

Anecdotal evidence shows that most women in prison have been abused at some point in their lives. Helen Mayo, a volunteer who has run a battered woman’s support group at the Central California Women’s Facility prison in Chowchilla, CA estimates that as much as 97% of women behind bars today have been victimized before, or in some cases during, their time in prison.

Anecdotal evidence shows that most women in prison have been abused at some point in their lives. Helen Mayo, a volunteer who has run a battered woman’s support group at the Central California Women’s Facility prison in Chowchilla, CA estimates that as much as 97% of women behind bars today have been victimized before, or in some cases during, their time in prison.

The bottom line is that our criminal justice system needs to look at the whole picture. Sending victims of abuse to prison only revictimizes them all over again. Community-based facilities and treatment programs offer alternatives to incarceration that are more likely to help victims of abuse break the cycle and make positive contributions to society.

The rising costs of the prison system

Budget shortfalls are forcing many states to take a long, hard look at their criminal justice systems. Over the last three decades the national war on drugs, as well as newer “tough on crime” sentencing guidelines such as California’s “three strikes” policy, have led to individuals spending their lives behind bars on charges of petty theft or drug possession. According to a March 23, 2010 New York Times article, “About 11 percent of the (California) state budget, or roughly $8 billion, goes to the penal system, putting it ahead of expenditures like higher education.”

Budget shortfalls are forcing many states to take a long, hard look at their criminal justice systems. Over the last three decades the national war on drugs, as well as newer “tough on crime” sentencing guidelines such as California’s “three strikes” policy, have led to individuals spending their lives behind bars on charges of petty theft or drug possession. According to a March 23, 2010 New York Times article, “About 11 percent of the (California) state budget, or roughly $8 billion, goes to the penal system, putting it ahead of expenditures like higher education.”

While California may be most dramatic example of a system that has spun out of control, many states are facing problems that cannot be solved by simply building more prisons. As the prison population ages and requires increased medical attention, the cost of incarcerating these individuals is soaring; Click image to enlargebuilding more prisons adds to those costs and addresses the symptom of the problem while ignoring the cause.

Identifying and releasing incarcerated survivors of domestic violence who pose no threat to society represents a real and significant way for states to reduce their prison populations. Additionally, bolstering measures to identify victims of abuse as they are accused of crimes can help prevent the injustice and added expense of sending victims to prisons in the first place. Every case must be looked at based on its individual circumstances, and abuse, where it is a mitigating factor in an alleged crime, must be examined.